WHICH IS BETTER, BSA vs. NON-FAT MILK, in WESTERN BLOT?

As a researcher, you may ask or be asked one of the most "popular" questions about setting up a western blot (WB). "Which blocking buffer/blocking agent do I use?" It's funny that whenever you think about this question, you may have many blocking reagents in your head and trying to figure out their pros and cons. But eventually, probably only BSA and non-fat milk (NFM) will become the default candidates in your answer. This interesting phenomenon demonstrates the popularity of BSA and NFM in WB and meanwhile reminds us to understand the key features of BSA and NFM more extensively.

We all know that a blocking agent is a non-reacting substance used to prevent the non-specific binding of your chosen antibodies to the nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. In general, the membrane has lots of hydroxy (OH) groups on its surface that helps reserve proteins through hydrophobic interaction with no specificity. After protein transfer, the free OH groups on the membrane are open to bind any proteins including the primary antibodies that will be applied in your WB assay causing unacceptable background. To mitigate the potential issue, protein components in NFM or BSA can help bind those free OH groups and in turn block the later interaction of primary antibodies and OH groups, resulting in a much cleaner WB background.

When you make your blocking buffer, the concentration of NFM or BSA can be tailored between 1-5% for your experiment. It's always safer to start with a lower concentration and slowly work your way up to 5%. For an intensely binding antibody, a 5% concentrated NFM or BSA will likely help significantly eliminate those infuriating false positives. Concentration higher than 5% is not recommended because your target protein also risks being blocked.

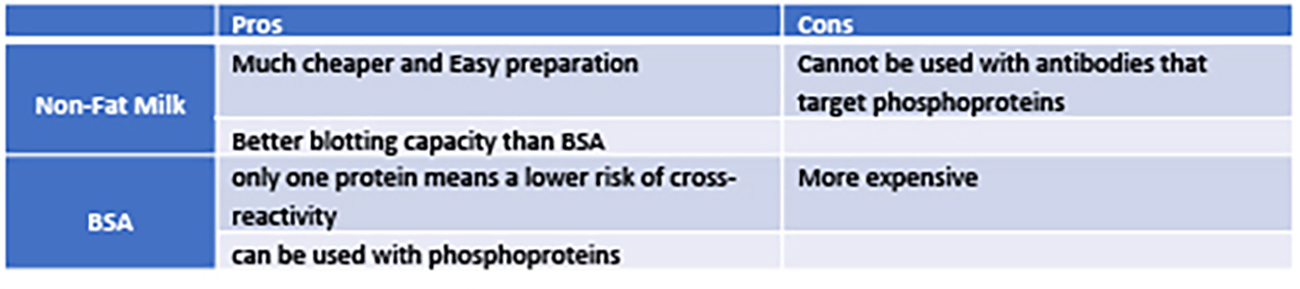

Many researchers choose to use NFM over BSA as their blocking agent because NFM is the cheaper and easier option. However, please be aware that BSA and NFM are not generally exchangeable since each has preferred application circumstances within a Western Blot. It would be better to determine which agent is more suitable for a particular assay. To this end, antibodies and proteins to-be-detected in WB should be considered.

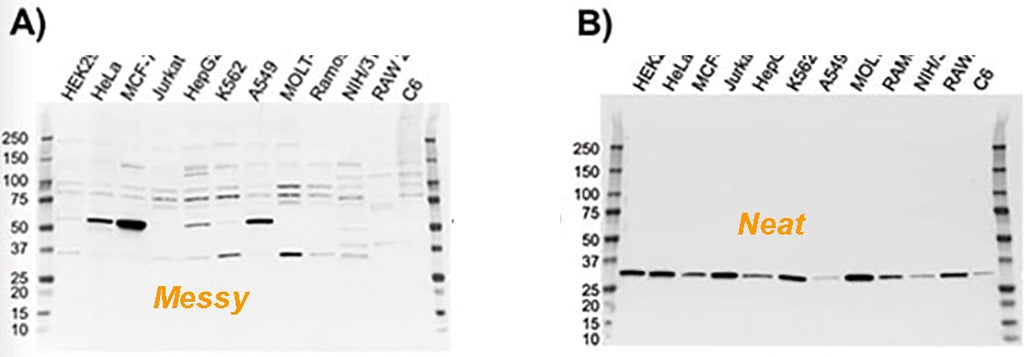

Is your protein of interest expressed at a high level? How strong is the binding affinity of your antibody? Answers to the two questions will be the first indicator to help you choose the blocking agent. Different antibodies have different binding strengths and specificity, and proteins to be detected are expressed at varying levels. For antibodies that are suspected to be more intensely/prominently binding and the target protein is expressed at relatively high levels, 5% NFM may prevent undue/promiscuous binding of the antibody, thus eliminating false positive signals in WB. But for antibodies with low binding strength, or their target proteins may be scarcely present in the cell, it is always better and safer to use BSA only because BSA is a single purified protein. In contrast, NFM constitutes a few mixed proteins that may hinder the actual antibody binding. Thus, the first rule of using NFM or BSA will simply depend upon your primary antibody nature and, of course on the availability of the target protein of your interest.

Notably, the above circumstance is only a general occasion. If the antibodies used in your WB are phosphor-specific antibodies, it is best to use BSA as the blocking agent since proteins such as Casein, which is the most abundant protein in milk, is a phosphoproteins and can indeed react with the phosphor-specific antibody via non-specific binding, thus debarring the actual intended signals and increasing the background.

In line with the previous discussion, we collected the key features of each blocking agent. Kindly note that due to the complexity of biology (diversity of biological samples and the complexity of assay conditions), the pros and cons only provide a guide to help your experimental design. The optimized protocol must be determined by multiple testing.