Biotin and its Application in Molecular Biology

Biotin, a member of the water-soluble B-complex group of vitamins, is essential for life. Interestingly, humans and other mammals cannot synthesize biotin de novo and therefore must obtain this vital micronutrient from dietary sources and gut bacterial metabolites. Nutritional biotin is absorbed in the small intestine, and the biotin deficiency is very rare since its daily requirement is low. The primary biological function of biotin in mammals is to act as a covalently bound cofactor for the biological activities of biotin-dependent carboxylases. These enzymes play pivotal roles in many essential biological processes such as lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, amino acid metabolism, and energy transduction.

Consumption of raw eggs regularly may cause biotin deficiency because of avidin, a protein present in raw egg whites. It has been postulated that avidin may serve as an antibiotic for eggs by binding to free biotin that invading bacteria require for survival. Avidin strongly binds to biotin, thus making biotin sequestered from being absorbed. Notably, in the 1960s, a new protein with a remarkably similar structure to avidin despite very limited amino acid homology was discovered from the bacteria Streptomyces and named streptavidin. Similarly, streptavidin also strongly binds to biotin and has been thought to serve as an antibiotic against competing bacteria. It has been revealed that the bond between (strept)avidin and biotin is one of the most robust noncovalent protein-ligand interactions found in nature. Once the bond is formed, it is unaffected by changes in pH, temperature, organic solvents, etc.

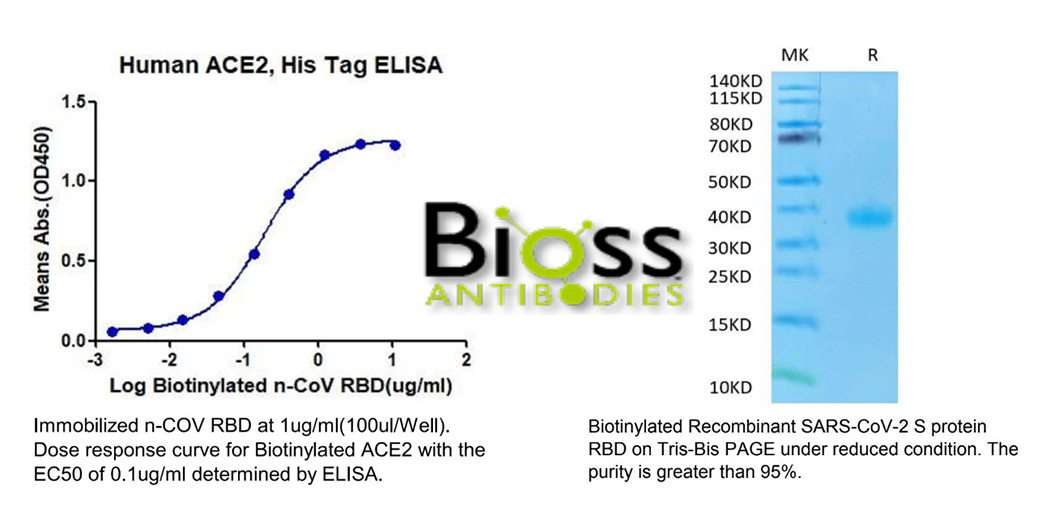

Biotin is a small water-soluble molecule. Its side chain is easy to manipulate to attach to other biomolecules, resulting in biotinylation (also known as biotin labeling). These unique physicochemical properties make biotin an interesting mediator to confer the ability of biotinylated targets to interact with avidin or streptavidin. The high-affinity biotin-(strept)avidin bond has become widely used in detecting and separating target proteins/cells. These applications include immunoassays (ELISAs and Westerns being the most popular applications), affinity chromatography, pull-down assays, supramolecular construction, targeting of cancer cells for drug delivery, and many others.

To utilize the natural binding of biotin and (strept)avidin, biomolecules of interest must be biotinylated first. To make the biotinylation more convenient, scientists have developed several methods to biotinylate biomolecules. Over here, we will briefly introduce two popular approaches to biotinylate proteins. One is to use biotinylation chemical reagents in vitro. The exposed side chain of biotin can be cross-linked to functional groups via specialized chemicals. Various chemicals have been used to help biotinylate the target of interest in different microenvironments. The most popular chemical for protein biotinylation is Biotin-N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester to target primary amines on target peptides.

The other popular way to biotinylate protein is to use the enzyme BirA in vitro or in vivo. BirA is the E. coli biotin ligase that site-specifically biotinylates a lysine side chain by recognizing a 15-amino acid peptide sequence termed Avi-Tag. Accordingly, scientists developed various vectors to express Avi-Tag fusion proteins, in which Avi-Tag is added to either the N or C terminus of the protein. Subsequently, commercially available BirA incubates with the recombinant proteins to enzymatically biotinylate them in vitro. Alternatively, we can also use BirA in vivo to catalyze protein biotinylation. To this end, BirA will co-expressed with the protein of interest fused to Avi-tag in bacteria, yeast, insect, and mammalian cells. Please keep in mind that protein solubility is critical to ensuring the biotinylation efficiency in the in vivo method.